Opster Team

Before you begin reading this guide, we recommend you try running the Elasticsearch Error Check-Up which analyzes 2 JSON files to detect many configuration errors.

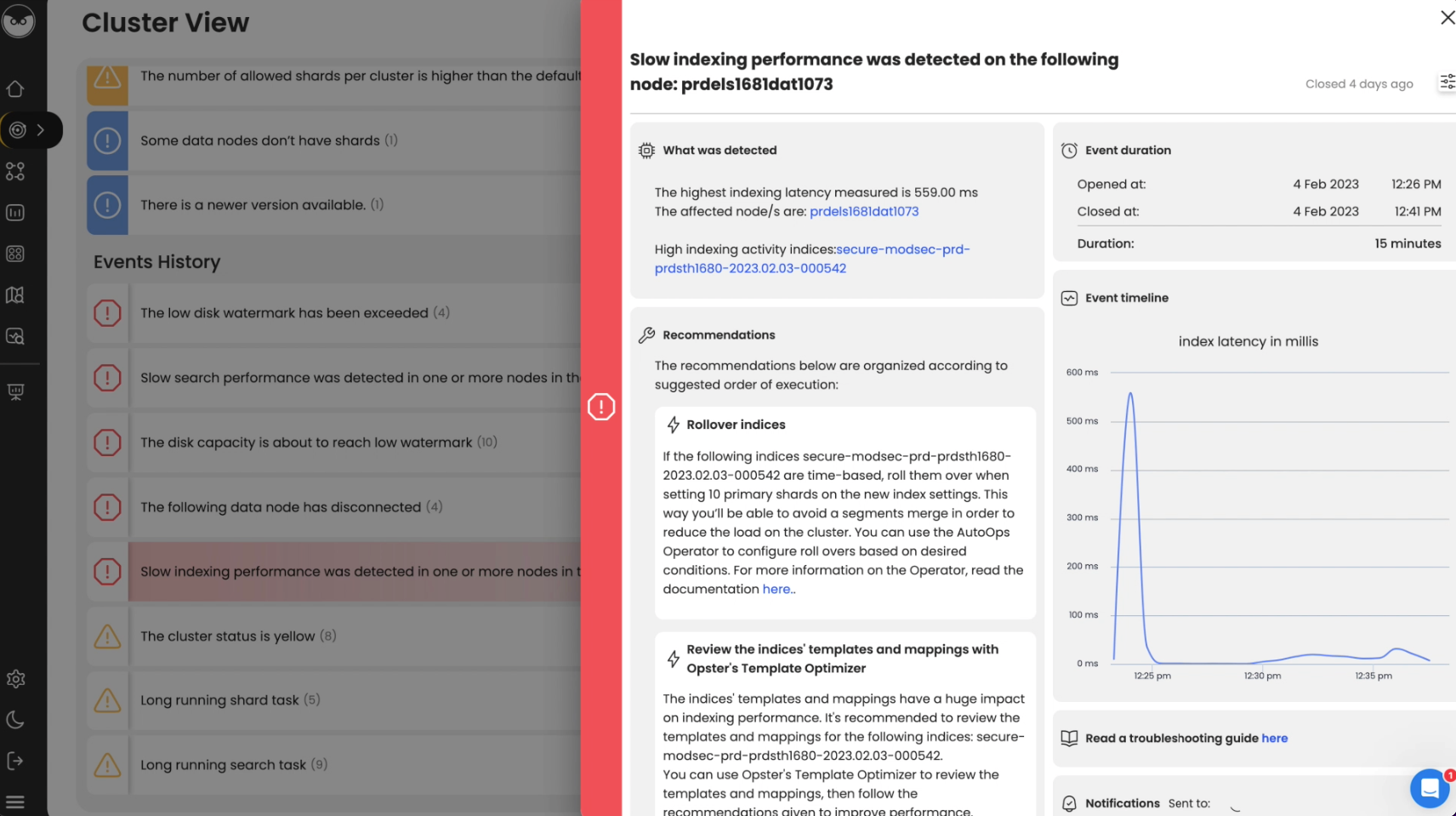

To easily locate the root cause and resolve this issue try AutoOps for Elasticsearch & OpenSearch. It diagnoses problems by analyzing hundreds of metrics collected by a lightweight agent and offers guidance for resolving them.

Take a self-guided product tour to see for yourself (no registration required).

This guide will help you check for common problems that cause the log ” Setting doc_values cannot be modified for field ” + name + ” ” to appear. To understand the issues related to this log, read the explanation below about the following Elasticsearch concepts: plugins and index.

Overview

A plugin is used to enhance the core functionalities of Elasticsearch. Elasticsearch provides some core plugins as a part of their release installation. In addition to those core plugins, it is possible to write your own custom plugins as well. There are several community plugins available on GitHub for various use cases.

Examples

Get all of the instructions for the plugin:

sudo bin/elasticsearch-plugin -h

Installing the S3 plugin for storing Elasticsearch snapshots on S3:

sudo bin/elasticsearch-plugin install repository-s3

Removing a plugin:

sudo bin/elasticsearch-plugin remove repository-s3

Installing a plugin using the file’s path:

sudo bin/elasticsearch-plugin install file:///path/to/plugin.zip

Notes and good things to know

- Plugins are installed and removed using the elasticsearch-plugin script, which ships as a part of the Elasticsearch installation and can be found inside the bin/ directory of the Elasticsearch installation path.

- A plugin has to be installed on every node of the cluster and each of the nodes has to be restarted to make the plugin visible.

- You can also download the plugin manually and then install it using the elasticsearch-plugin install command, providing the file name/path of the plugin’s source file.

- When a plugin is removed, you will need to restart every Elasticsearch node in order to complete the removal process.

Common issues

- Managing permission issues during and after plugin installation is the most common problem. If Elasticsearch was installed using the DEB or RPM packages then the plugin has to be installed using the root user. Otherwise you can install the plugin as the user that owns all of the Elasticsearch files.

- In the case of DEB or RPM package installation, it is important to check the permissions of the plugins directory after you install it. You can update the permission if it has been modified using the following command:

chown -R elasticsearch:elasticsearch path_to_plugin_directory

- If your Elasticsearch nodes are running in a private subnet without internet access, you cannot install a plugin directly. In this case, you can simply download the plugins and copy the files inside the plugins directory of the Elasticsearch installation path on every node. The node has to be restarted in this case as well.

Index and indexing in Elasticsearch - 3 min

Overview

In Elasticsearch, an index (plural: indices) contains a schema and can have one or more shards and replicas. An Elasticsearch index is divided into shards and each shard is an instance of a Lucene index.

Indices are used to store the documents in dedicated data structures corresponding to the data type of fields. For example, text fields are stored inside an inverted index whereas numeric and geo fields are stored inside BKD trees.

Examples

Create index

The following example is based on Elasticsearch version 5.x onwards. An index with two shards, each having one replica will be created with the name test_index1

PUT /test_index1?pretty

{

"settings" : {

"number_of_shards" : 2,

"number_of_replicas" : 1

},

"mappings" : {

"properties" : {

"tags" : { "type" : "keyword" },

"updated_at" : { "type" : "date" }

}

}

}List indices

All the index names and their basic information can be retrieved using the following command:

GET _cat/indices?v

Index a document

Let’s add a document in the index with the command below:

PUT test_index1/_doc/1

{

"tags": [

"opster",

"elasticsearch"

],

"date": "01-01-2020"

}Query an index

GET test_index1/_search

{

"query": {

"match_all": {}

}

}Query multiple indices

It is possible to search multiple indices with a single request. If it is a raw HTTP request, index names should be sent in comma-separated format, as shown in the example below, and in the case of a query via a programming language client such as python or Java, index names are to be sent in a list format.

GET test_index1,test_index2/_search

Delete indices

DELETE test_index1

Common problems

- It is good practice to define the settings and mapping of an Index wherever possible because if this is not done, Elasticsearch tries to automatically guess the data type of fields at the time of indexing. This automatic process may have disadvantages, such as mapping conflicts, duplicate data and incorrect data types being set in the index. If the fields are not known in advance, it’s better to use dynamic index templates.

- Elasticsearch supports wildcard patterns in Index names, which sometimes aids with querying multiple indices, but can also be very destructive too. For example, It is possible to delete all the indices in a single command using the following commands:

DELETE /*

To disable this, you can add the following lines in the elasticsearch.yml:

action.destructive_requires_name: true

Log Context

Log “Setting [doc_values] cannot be modified for field [” + name + “]”classname is Murmur3FieldMapper.java We extracted the following from Elasticsearch source code for those seeking an in-depth context :

throws MapperParsingException {

Builder builder = new Builder(name);

// tweaking these settings is no longer allowed; the entire purpose of murmur3 fields is to store a hash

if (node.get("doc_values") != null) {

throw new MapperParsingException("Setting [doc_values] cannot be modified for field [" + name + "]");

}

if (node.get("index") != null) {

throw new MapperParsingException("Setting [index] cannot be modified for field [" + name + "]");

}

Find & fix Elasticsearch problems

Opster AutoOps diagnoses & fixes issues in Elasticsearch based on analyzing hundreds of metrics.

Fix Your Cluster IssuesConnect in under 2 minutes

Arpit Ghiya

Senior Lead SRE at Coupa